If the Starlink debate has done anything, it has rekindled South Africa’s long-running, anguished and contested debate about Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) and affirmative action.

Confronted with either “equity equivalents” or equity-stake BEE, the South African government will effectively be choosing between implementing modern technology providing an increasingly vital service to rural people on the one hand - or sticking to its BEE guns on the other. It feels very like it's an either/or decision, because Starlink’s owner Elon Musk has complained bitterly that he is not allowed to invest in SA because he is white - an overstatement, but you know, you get the point.

Where do you even start in the BEE debate? The obvious opening point is that SA is a complex place, with competing needs and goals: economic growth on the one hand and racial redress on the other.

But even this one issue is contested. In parliament recently, President Cyril Ramaphosa said that contrary to opposition party claims, BEE is not the problem holding back the SA economy. Economic concentration is the big problem.

This “concentration” issue is an old bugbear of the ANC’s, and something of a misnomer. But Ramaphosa cited reports from the mountain tops of economic knowledge: IMF and the World Bank.

Daily Maverick journalist Rebecca Davis fact-checked this claim, noting that Ramaphosa didn’t actually mention which IMF and World Bank reports he was relying on.

But it so happens that both the IMF and the World Bank issued reports on SA earlier this year, here and here.

As Davis points out, the reports quasi-support both sides of the debate. The World Bank report did actually identify BEE as a potential “market distortion” which has “not been evaluated for effectiveness”. While the report did not call for BEE to be scrapped, it punted enthusiastically the notion of equity alternatives to the ownership regulations of BEE.

Chalk one up for Starlink!

“Streamlining firm entry and operational prerequisites related to the 2013 B-BBEE for foreign investors by making systematic use of Equity Equivalence Investment Programs when investors commit to train Black workers and develop supply chains with local businesses. While the B-BBEE is well intentioned, managing required scorecards places a heavy burden on public administration and foreign companies.”

The IMF report, on the other hand, did give Ramaphosa some support: “ … high market concentration in several sectors, including manufacturing and banking, has inhibited the emergence of smaller firms that create new jobs. High labor costs, skills mismatches, and regulated hiring and firing practices have further contributed to high unemployment and low productivity growth,” it said.

The problem is that the IMF is centrally concerned with fiscal probity rather than government policy, so the concentration idea is a bit of a throwaway line amid all the data about something called “TFP growth”. That’s “total factor productivity” for the jargon junkies, and there are several helpful mathematical formulas provided for calculating it.

The other problem is that this report, part of something called its “Article IV Consultation process”, is expressed in a kine of code very specific to the IMF. Anybody who is familiar with the IMF knows this organisation in which every idea is strenuously contested from all sides of the political spectrum, with endless economic debates accompanying its every tiny expression. The result is that when it does actually say something, especially in public documents, it tends toward the totally unintelligible.

For example, the report says: “Additional well-sequenced business-environment, governance, and labor-market reforms aiming at closing structural gaps relative to peers can help support investment and job creation, particularly in SMEs, generating substantial output gains and helping reduce inequality”.

Would “business-environment, government and labor market reforms” be a coded way of saying BEE is a problem? You could read it as saying so, or not, depending on your prejudice and whether you were lucky enough to get a secret decoder ring in your Christmas cracker. The same applies to the phrase “reducing excessive red tape” which has been all over IMF reports since the year dot.

Outside of this debate, two big political changes have taken place in the BEE space. One is that the ANC is massively doubling down on BEE, with an intensity that South Africans are not, I suspect, fully or generally aware. And the other is that political opposition to BEE is expanding and intensifying, partly in response to the above.

The changing fact of BEE

It's important to get basic principles right here. There has always been strong support for BEE and there has always been strong opposition to it. But recently several things have changed.

- Politics has changed. In the wake of SA’s miraculous transition, the notion of BEE was widely supported not only in the political sphere but also by unions and business. It was then seen as entirely logical requirement and indeed had explicit constitutional support.

But SA’s low growth rate over the past 15 years, has sparked a new search for the causes of this chronic state. BEE is now seen more widely as one of the reasons or at least a contributor to this low growth. This was in part precipitated by the BEE coefficient during the State Capture phase. Almost every particular instance of state capture, from the VBS scandal to the Transnet train appropriation disaster, was associated with a BEE scheme. BEE opened the door to specialist treatment and overriding considerations that allowed insiders to manipulate contracts in their favour. Whatever other good or bad it has done, BEE is now widely seen as the passport to corruption.

- The law has changed: Initially, BEE was almost taken for granted as a necessary precondition for doing business in SA, understandably because of the historic deliberate econmic degradation of SA’s black population. But two court cases on BEE have effectively placed some restraints on empowerment in an attempt to balance different rights ascribed by the constitution.

These are both pretty old, but they are both going to become very important soon.

The first is Minister of Finance v Van Heerden decided in 2004. The facts were that parliament adopted new pension laws in 1996 that provided more generous benefits to “previously disadvantaged” members of Parliament (particularly Black MPs who served under apartheid or in homelands or liberation movements). Van Heerden, a white former MP, challenged these provisions, arguing they were discriminatory and violated his right to equality under Section 9 of the Constitution.

The court rejected the idea that all differentiation based on race or similar grounds is automatically suspect simply because of the existence of a clause guaranteeing equality. But it established a three-part test for evaluating affirmative action measures: the differentiation has to target persons or categories of persons who have been disadvantaged by unfair discrimination: it must be designed to protect or advance these people, and it must promote the achievement of equality.

There is quite a lot of verbal guff there, but essentially the court was saying affirmative action must be carefully constructed to meet legitimate goals, not arbitrary or capricious objectives. Even at this point, it's interesting to note there was a minority judgement which suggested the court was uncomfortable with this formulation as veering too far away from the idea of pure equality.

The second case went a bit further. In 2016, the Constitutional Court found in Solidarity v Department of Correctional Services that using national demographics alone to set employment equity targets violates the equality clause since regional population demographics are ignored and individual circumstances are not considered.

Essentially, affirmative action must be flexible, context-sensitive, and not mechanical. And it confirmed that individual rights to dignity and fair treatment cannot be overridden by abstract group targets.

This was where the simplified rule, “targets not quotas” arose, much the same as the findings of American courts on the same questions some years ago - rules which significantly have now been generally scrapped or overturned.

- The institutional economic backdrop has changed. Academic economic opposition to BEE used to be the preserve of liberal organisations like the Institute of Race Relations. A former member of the institute, Anthea Jeffery published a book in 2014, called “BEE: Helping or Hurting?”. She concluded the latter. But her support in SA academia was at the time zero.

Today however mainstream academics are much more critical of BEE and affirmative action. Only last month William Gumede, Associate Professor: School of Governance at the University of the Witwatersrand, authored an article with a title leaving little room for misunderstanding his position: "BEE is killing the economy and must be ditched" he wrote in the Sunday Times. He argues that the current BEE framework has primarily benefited a politically connected elite, fostering corruption and hindering genuine economic transformation. There have been other voices of course in favour of BEE, but the grounds of the debate have shifted.

The charge that BEE only helps the elite has been laid at the door of BEE now for years and was one of the motivations for broadening the initial idea of equity-based BEE for something more back in the early 2000s. The change means that BEE now includes equity ownership, but also targeted management, human resource development, preferential procurement, and enterprise development. All of this was classified under the heading Broad-based black economic empowerment, or B-BBEE.

But even this wider system has come under pressure from academia, with the hallowed old concept of the “unintended consequences” becoming more and more cited.

- Time has passed. My sense is that because a new generation of professionals is entering the workforce and the size of the black middle class is growing, except for a narrow band of very politically motivated individuals, the public view of BEE has altered. It was one thing to champion BEE at the time of the transition to democracy but now 30 years later, attitudes they are a-changing.

In April this year, an Ipsos Survey found that 36% of South Africans oppose BEE, 44% support it, and 20% are undecided. The change follows pretty closely the decline in the support of the ANC, and the emergence of new political forces, which have different priorities. MK notionally supports “empowerment” but as a rural party, it has different priorities. The fracturing of political parties means the voices in favour and against BEE are now more varied.

So the big question is this: why in the context of a weak economy and changing political dynamics, is the ANC doubling down on BEE?

One reason is that its existing policies just don’t seem to have worked, leading the party to up the ante. The most obvious example is the Employment Equity Amendment Act which empowers the Minister of Employment and Labour to set sector-specific numerical targets for the representation of designated groups, namely Black South Africans, women, and persons with disabilities, in various occupational levels within companies.

This goes back to the question in the Solidarity case: what constitutes a target and what constitutes a quota? The DA’s position is that the legislation violates the right to equality, imposes inflexible hiring practices that disregard the availability of qualified candidates, and grants excessive discretionary power to the Minister without sufficient checks and balances.

The government defends the amendment, arguing that these are not rigid quotas because the minister’s powers of exercise are in consultation with stakeholders and subject to oversight. Most of all, they are necessary for achieving substantive equality and redressing historical injustices and designed to address persistent disparities in workplace representation.

Well, the ANC is certainly right about the fact that the disparities have been persistent. SA’s Commission for Employment Equity has found that white people occupied 65.9% of top management-level posts. Compared to listed companies, that’s actually kinda low: 90% of CEOs in the JSE Top 40 companies are white.

Why no change?

How is it possible that this hasn’t changed significantly in 30 years despite all this BEE legislation?

To me, It may still be a bit early to make definitive judgments about the efficacy of BEE legislation at this level. Earning the skills and the promotions in big companies does take time: many of the white CEOs of the Top40 companies started their careers 30 years ago.

The same Commission for Employment Equity report, which by the way is a little light on statistical fidelity (its total reporting base is only 7.5 million people for example), finds the proportion of white managers declines as you drop down the hierarchy; only 30% of senior management are white male, for example.

My guess is that the risks involved in choosing the CEO are so huge that there is always a bit of inertia.

My own experience of businesses in South Africa is that managers are acutely aware of the shortage of black people in senior ranks, and do generally try to right the balance. The notion that white managers are actively keeping out black managers is, broadly speaking, bunk. But on the other hand, nobody in the private sector really yearns to discriminate on the basis of anything other than talent and skill, even - and perhaps particularly - the potential beneficiaries of BEE.

The point is that this is all coming to an inflexion point. If you simplify it, for white South Africans generally, the failure of BEE means it hasn’t worked and should be scrapped. For black South Africans generally, the failure of BEE means it hasn’t worked and should be intensified.

Is it possible that neither is right? SA needs to find a way to be more patient, recognise the complexities and unintended consequences, and find a way to focus as much on economic growth than on diverting and divergent legislative interventions.

Transformation is just so much more difficult in times of economic decline; that much at least should be obvious. 💥

From the department of a certain pecking order ..

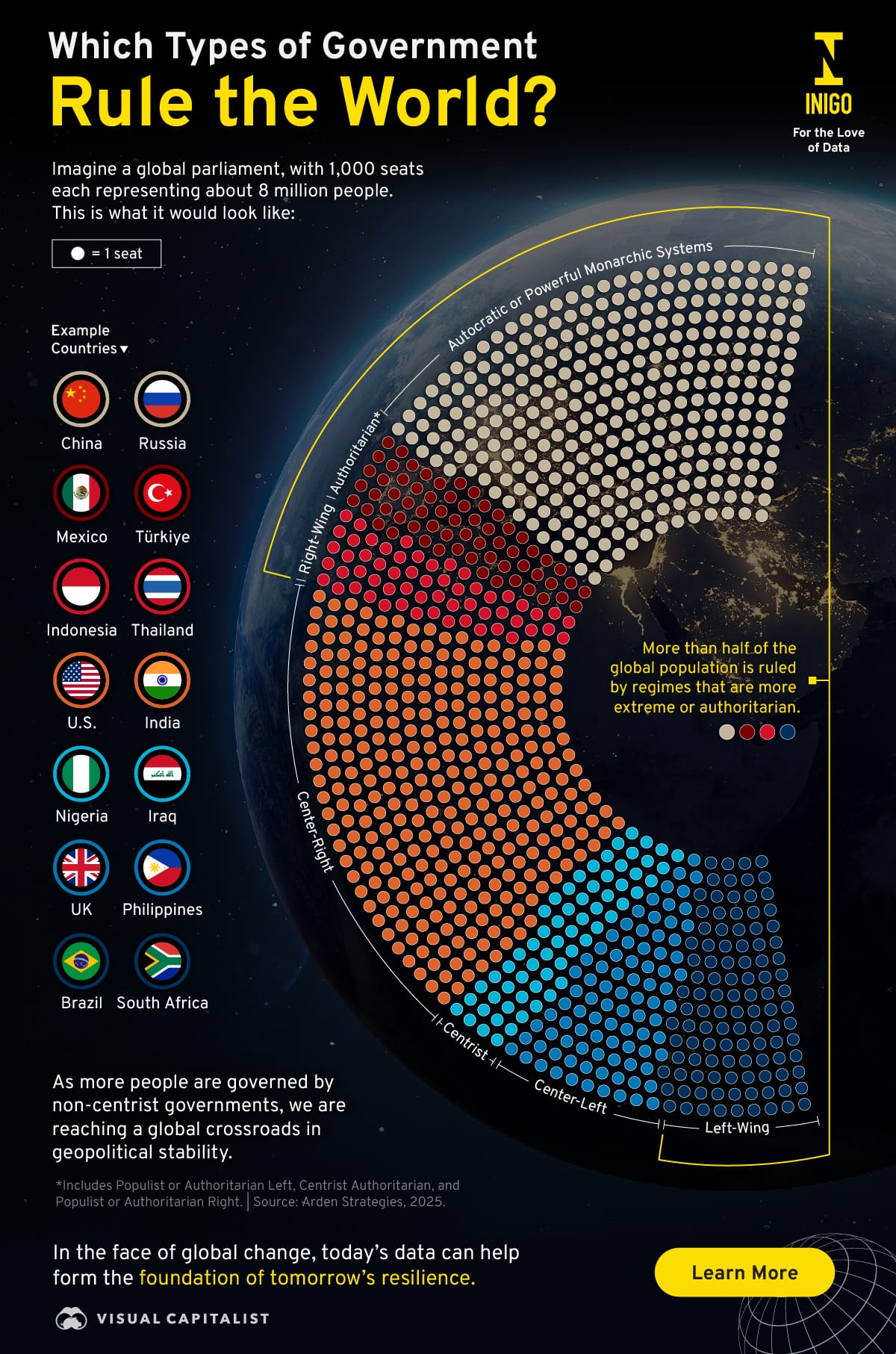

From the department of the centre not holding ..

From the department of what could possibly go wrong ..

From the department of you cheddar believe it ..

Thanks for reading - please do share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value this blog and ask them to add their email in the block below - it's free for the time being. If the sign-up link doesn't appear, you'll find it on the site.

Till next time. 💥

Join the conversation