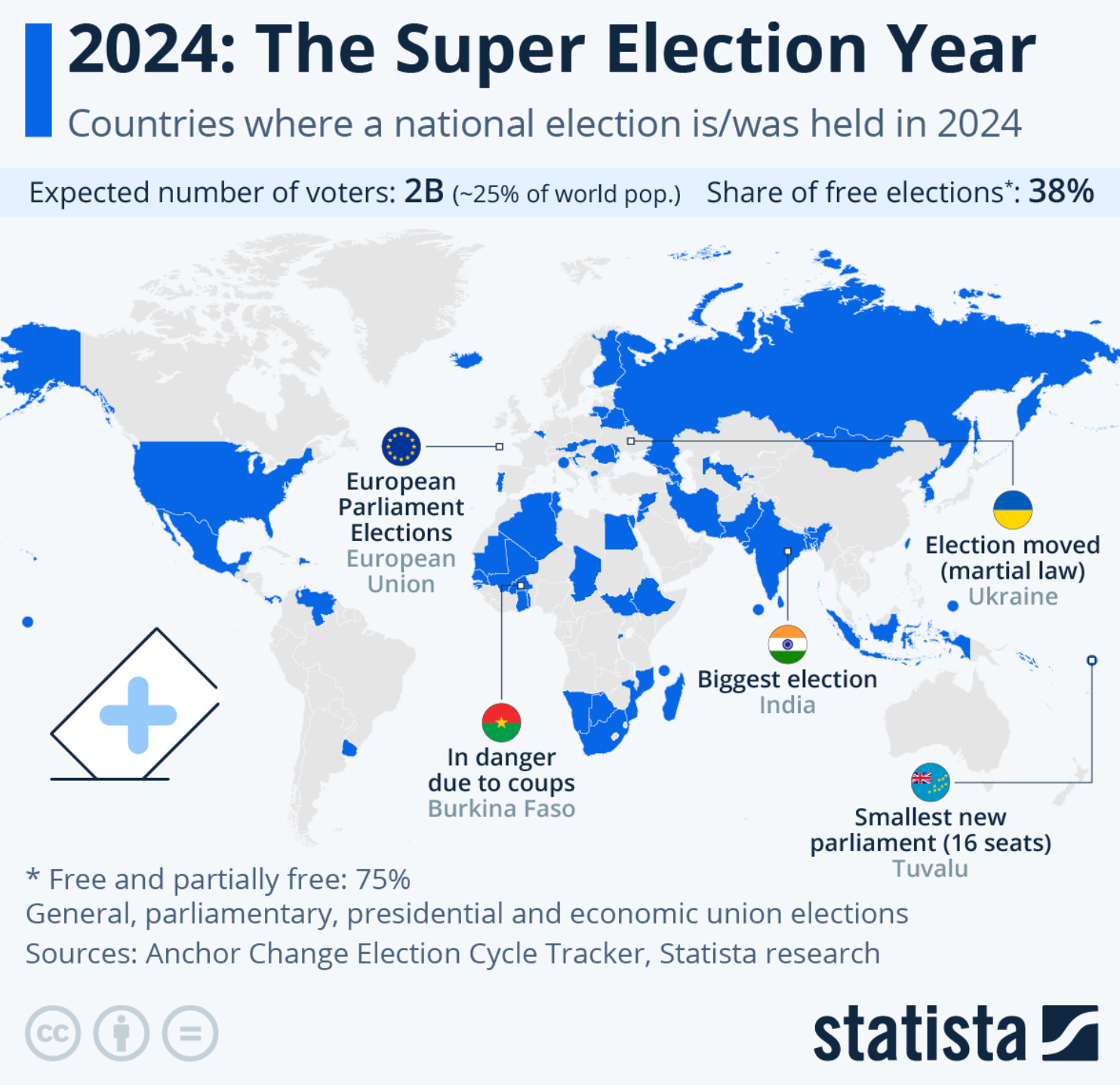

The year of our Lord two thousand and twenty-four was designated at its start to be the year of democratic elections. These past twelve months set a record for the largest number of votes cast in democratic elections in a single year. The world’s four biggest democracies, India, Indonesia, the United States, and Pakistan all went to the polls, as did 27 EU member states electing the new European Parliament. There were elections in over 70 countries, inhabited by half the human race.

So how did that all go? Er … not so well.

To answer the question, we (obviously) need to go to Sri Lanka. Late this year, the island off the coast of India held two elections in quick succession. In a shock result, the head of the National People's Power coalition, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, known popularly as AKD, won the presidency on September 21.

The first thing he did was call snap elections, which were held on November 14 and his party not only won but won more seats than any Sri Lankan political party in history and won every district except one. The election also saw a record number of women MPs elected (21 - not that impressive TBH) and a record number of first-timers (150 - which is impressive). In the previous election, the NPP got just more than 3% of the vote.

For Sri Lanka, all this would be dramatic enough in itself but even if you know only the barest outlines of the island’s history (like moi!) it becomes apparent this is not just a big day in politics but a political earthquake. Politics there has been dominated by two parties since independence from Britain in 1948: the Tamil-dominated Itak (Tamils are a minority - there was a separatist insurrection movement which ended in 2009) and the social democrats, the SJP. But more than that, it's been dominated by two families, the Bandaranaikes and the Rajapaksas.

SWRD Bandaranaike was prime minister in 1956 but he was assassinated; his wife, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, then served three terms and his daughter Chandrika served one.

Mahinda Rajapaksa served as president and prime minister, his brother Gotabaya was president but resigned in 2022, while his other brother, Basil (and a whole bunch of family members), were ministers during the 2022 financial crisis. Gotabaya actually fled the country, resigning by email, at the height of the crisis.

The political earthquake doesn’t end there. The leader and now president AKD was a Marxist revolutionary and worked for a time for an insurgency group as a student. He then became a neo-Marxist, working within the parliamentary system, and was elected on an anti-corruption and pro-poor ticket. So now that he is president, how do we classify him now?

Well, as a free-market capitalist, obvs. The Colombo-based pro-market think tank Advocata Institute said that Dissanayake "now advocates for a pro-trade approach, emphasising the simplification of the tariff structure, improving the business environment, reforming tax administration, ending corruption and positioning the private sector as the engine of growth”.

Isn't that just … well … so 2024? The simplistic view of elections this year is that a) they have gone stunningly well in the sense that huge numbers of votes have been cast and b) incumbent parties got thumped everywhere. But it is deeper than that because what has been missing in elections around the world is tradition. It's perhaps most obvious in the US, which is so much part of the world’s consciousness. Early in the US campaign, the leaders of the US Republican Party were, I suspect, a little goosey about nominating Donald Trump, who had lost the previous election and was, well, tainted. So they threw a whole bunch of candidates at their supporters, only for candidates to fall over like skittles and for Trump to blow them away. And then he won the election itself.

But something else is obscured by Trump’s dominance of the headlines. Trump wasn’t the only one to win: the Republicans not only consolidated their narrow majority in the House but flipped the Senate. The Democrats, not exactly the incumbents but close to it, got thumped across the board.

In this sense, the result of the US election is comparable to the UK election, the Botswana election, the Japan election, and the Ghana election, to name just a few. Since the pandemic hit in 2020, incumbents have been removed from office in 40 out of 54 elections in Western democracies. Steven Levitsky, a political scientist at Harvard University is quoted as saying by the Associated Press, “This reveals “a huge incumbent disadvantage,” he said. You don’t say.

Even where countries didn’t change governments, incumbent parties got thumped, like in France and of course in SA where the ANC dropped below a plurality. The big surprise in this category to me was Namibia: SWAPO did get a majority with 56% of the vote, but that was down from 87% in 2014. I mean, Swapo was basically supported by everyone and then it lost half the country!

The interesting thing about the anti-incumbent trend was that it was apolitical. In some countries, voters voted left (UK), in others right (US), and in still others, both ways simultaneously. Hello, France. But always against the incumbents.

The Financial Times columnist John Burn-Murdoch pointed out that every political party defending their record in government in the last twelve months lost vote share, some catastrophically; the U.S. Democratic Party’s slippage of 3.7 percentage points is comparatively mild compared to the British Conservatives, who declined by almost 20% from their 2019 vote. “The incumbents in every single one of the 10 major countries that have been tracked by the ParlGov global research project and held national elections in 2024 were given a kicking by voters. This is the first time this has ever happened in almost 120 years of records”.

The exceptions to this trend played out in Algeria, Azerbaijan and Rwanda. And what is the common factor here? It's what they call “heavily managed elections”. Which would be funny, if it were funny. Spain and Mexico were the real exceptions that proved the rule.

And it hasn’t finished by the way. Ireland is probably going to join the party this weekend; the ruling Fine Gael party has fallen from first to third in the polls. Germany’s Social Democrat-led coalition is historically unpopular and was forced to hold early elections next February. Incumbents in Canada and Australia are also heading in the same direction next year.

The given reason for this anti-incumbency trend, in simple terms, is that this year, household economics dominated. Inflation was a big issue and rising prices always hit the government in power. Obvs.

But I suspect it's a bit more complicated. People are just generally pissed off. The AP mentioned story above quotes Rob Ford, professor of political science at the University of Manchester, who argued that although inflation was the proximate cause, the issue is broader and more diffuse.”

“It could be something directly to do with the long-term effects of the COVID pandemic — a big wave of ill health, disrupted education, disrupted workplace experiences and so forth making people less happy everywhere, and they are taking it out on governments,” he said.

“A kind of electoral long COVID.” Very funny.

Some people think the issue is much more sinister, or at least more ominous. Others think inflation was a factor but culture and other economic factors should not be dismissed. Mehreen Khan, Economics Editor for the UK’s Times, writes that the salience of inflation cannot be disentangled from other economic variables such as real wage losses, broader indices of the cost of living like rents and house prices, and trust in political parties to create fairer economic conditions.

Part of her reasoning is that in their analysis of the results, incumbent parties tend to focus on inflation at least partly to give themselves a free pass. If inflation is to blame, over which they had little or no control, then obviously they and their policies and decisions were not.

True, but still but inflation can’t be sidelined either. It was incredible to me how little effort incumbent parties made to explain why inflation was hitting everyone’s wallet and in particular, its global nature. The fact is that was an international event, it lifted prices for consumers rich and poor, it required big increases in interest rates, and it effectively reduced productive government spending since debt cost more. Frankly, I was amazed at the global acceptance by governments that interest rates had to go up; there was surprisingly little whining about it.

It reminds you of that famous quote in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis by Jean-Claude Juncker, then the prime minister of Luxembourg, who complained that “we know what to do—we just don’t know how to get re-elected afterwards.” In this case, they knew what to do, they did it, and they didn’t get reelected.

From the department of I.am.not.making.this.up.but.I.wish.I.was

Drinkable mayo comes to Japan

🤢 The product contains milk, ‘dairy-type products’, and mayonnaise seasoning. Which is putting it kindly.

From the department of turning on a dime - literally

GameStop has not remotely stopped at all

GameStop was the poster child of meme stocks, but the end story is even more weird; it has used the rapid inflow of investor capital not to create a better retail outcome but… to become a short term T-Bill warehouse.

The stock in the meantime continues to surge

From the department of seriously unhealthy practices

UnitedHealthcare CEO killed by a ghost. Seriously.

The killing of US UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson has become a mesmerising news moment, partly because it just keeps getting weirder. The arrested suspect Luigi Mangione was found Monday carrying something called a "ghost gun": a gun that had some parts made in a 3-D printer.

Thompson was shot outside a Manhattan hotel by a man using a 9mm handgun and silencer,and the shooting was caught on surveillance cameras. It turns out the weapon might have been a "ghost gun" used typically because it has no sales record, no serial number, and buyers are not required to undergo background checks.

The larger story is the inclination of healthcare companies to resist claims from high-expense customers. But there are other repercussions too, and one is executive security and insurance which is sure to explode. Turns out only 28% of S&P 500 companies provide security for one or more executive. Median spending has doubled but its still only $100 000 per year. According to reporting documents, the most paranoid company is Meta, which spent $24.39-million, more than triple the next highest spender, Alphabet, which came in at $6.78-million.

UnitedHealthcare, er, spent zero last year. That, presumably, will change.

Many thanks for getting this far! Please do share with anyone that might be interested.

Join the conversation