What is it about clubs? People love to be asked to join but are less enthusiastic about participating and the allure soon wears off.

Comedian Groucho Marx famously said he didn’t want to belong to any club that would have him as a member.

Just for the historical record, although the exact phraseology differs and the club concerned is not clear, it should be noted he was leaving a club not refusing to join. His comment was, notionally at least, made in a letter of resignation to the Friars’ Club in which he said, “I don’t want to belong to any club that would accept me as one of its members.”

The Friars Club was a private club in New York famous for its risqué roasts. Its membership was composed mostly of people who worked in show business. Several other clubs sought members from the Broadway set, including the Lambs Club and the Players Club. Marx’s friend and fellow wit George Kaufman distinguished them, saying: “The Players are gentlemen trying to be actors, the Lambs are actors trying to be gentlemen, and the Friars are neither trying to be both”.

Given that description, it's easy to speculate that Marx had different reasons for resigning than the paradoxical nature and self-deprecation implicit in the one he stated. But in a deeper sense, Marx pinpointed the problem with clubs; it's hard to know what they are for, or even what they actually do.

South Africa is about to become the head of what is perhaps the ultimate club: the G20. President Cyril Ramaphosa officially takes charge of the Group of 20 on December 1 after the baton is handed over from Brazil. SA takes over at a time of enormous international stress, so for SA’s diplomats, it constitutes something of an opportunity. But, if we are being honest, the chances of anything concrete being achieved are even smaller than the very little that is normally accomplished.

The first thing to know about G20, or Group of 20, is that it consists of 21 governments - first irony there. The group consists of 19 sovereign countries, the European Union, and the African Union. It's the ultimate club mainly because it accounts for 85% of the gross world product, 75% of international trade, and 56% of the global population.

Its main competitors are of course the G7, the Brics group, the UN, and a variety of regional groups including Asean. The G7 is really what we call “the West”; Europe’s main economies, Japan, Canada and the US. Think representative democracy, developed countries, etc.. The UN is the club of everyone. And the Brics group is … God knows, China and its frenemies maybe.

Because the UN is ungovernable and discombobulated, and because the G7 is too concentrated and like-minded, the G20 has emerged as the kind of place where meaningful deals can be done between countries which are not necessarily on the same wavelength. Just for example, it's one of the few bodies that includes the US, Europe, Russia, China, India and Indonesia. But just because they can strike deals, doesn’t mean they will.

Notionally, the advantage of G20 membership is that it provides a platform for shaping the global economic agenda and is evidence of what diplomats call “soft power”. It's the go-to forum for solving big international crises, like financial shocks, pandemics, or climate change. And with more of them emerging, the utility of the G20 is increasingly being underlined - and tested.

But in the end, it is just a club. There is no enforcement mechanism and the opportunity for building coalitions is more notional than actual. Brazil tried to make action against global warming a feature of its presidency, and President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva urged G20 nations to accelerate efforts to stave it off, suggesting advanced countries move their emissions reduction targets up to 2040 or 2045. You can’t help feeling that with Donald Trump in the White House next year, this idea is not going to fly very far. But Brazil did launch a platform to attract foreign investment in sustainable development, initially focusing on a portfolio of $8-billion in private-sector projects. And there were other innovations.

For South African diplomats, this is a moment to try to understand the current political moment and try to think of creative ways to decrease global tensions. With the best will in the world, I honestly wish them all the Singaporean luck because 2025 promises to be a year when the global world drifts further apart.

It's not just Trump’s obsession with the US trade deficit, or China's obsession with developing regional power, or even Russia’s war with Ukraine and Israel's war with everyone around it. Something more fundamental is going on.

It's worth taking a moment to capture the present moment. Call it going back to first principles in the art of diplomacy. Forgive the grotesque simplifications here, but we all have lives to live, so let’s take it as given that it is all much more complicated than I’m describing here.

Let’s assume for argument's sake there are two essential theories that are poles apart. The first is that history is over - not literally, of course. It was famously expounded by American political scientist Francis Fukuyama way back in 1992. Written just after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, Fukuyama speculated that Western liberal democracy and market capitalism might be universalising, and could be the final form of human government. Let’s call this the hopeful theory.

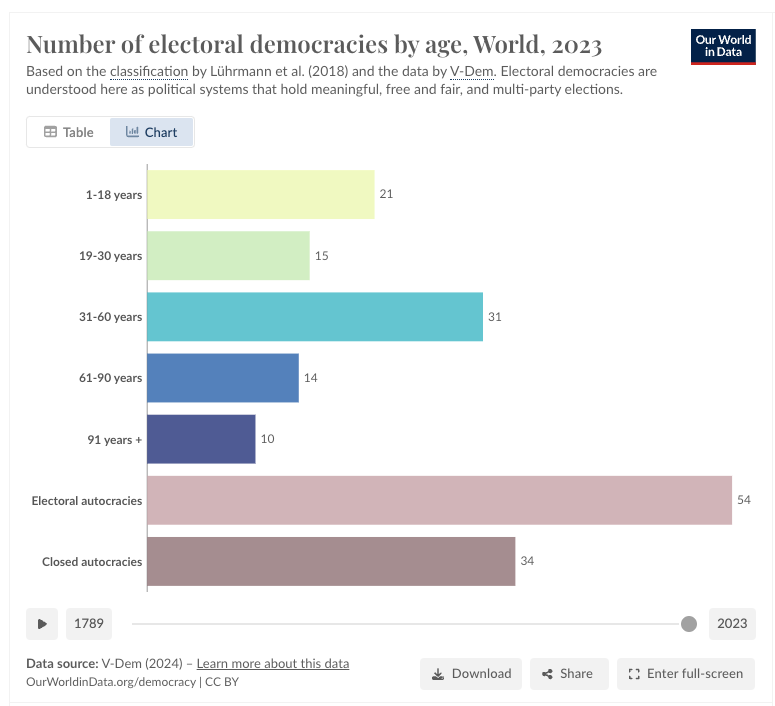

Seen in its time, it's easy to see why this idea took off. In 1989 there were 19 democracies under 18 years old. One year later, this number almost doubled to 34. By 1994, this increased further to 46. The total number of democracies overtook closed autocracies in 1989, and the total number of democracies increased to 90 in 2009: that’s almost double the number there were in 1989. Hallelujah!

But then it just got stuck. The number currently stands at 91. In the space of 15 years, we have added precisely one new democracy to the global total. So, we have seen both a dramatic increase in democratic systems over the past 30 years and also the stagnation of the trend. What happened is not, as Fukuyama seemed to suggest, that countries progress in a Marxian way up the ladder of human progress. The opposite seems true. The countries becoming democracies were much more likely to be closed autocracies than what we might call electoral autocracies. There were 49 electoral autocracies in 1989; there are 54 today.

After the boom of the 90s, authoritarianism was resurgent in the East and populism in the West. This happened despite, or perhaps because of, a massive increase in global prosperity. Either the population of the world is trading off economic prosperity against democratic rights, or the link between democracy and market capitalism is not as strong as we - or Fukuyama - thought.

So new era, new theory.

There is a lot of competition here, but what about, just for argument’s sake, American political scientist and international relations scholar John Mearsheimer's idea of “offensive realism”? The theory goes something like this: the primary goal of states is survival and that requires power maximisation. But they operate in an anarchic international system, where there is no overarching arbiter.

In this context, it makes sense to seek international dominance, or at least, regional hegemony, particularly given the inherent uncertainty about other states' intentions. In the era of US international dominance, acting according to liberal, human rights notions of international relations made sense, because there was a single overarching arbiter - the US.

Ironically, now that the Cold War is over for a bit, the result has not been global peace. Acting rationally, Mearsheimer would say, states around the world are seeking regional hegemony in their quest for security. Hello Ukraine, Taiwan, and even Gaza. More than that, populations within states are increasingly voting for politicians who manifestly protect their own as the overwhelming priority, which is one of the reasons why immigration has become such a global issue.

Mearsheimer doesn’t himself endorse this view, by the way, that’s why his most famous book is called “The Tragedy of Great Power Politics”. It's just the way of the world, as it currently stands. It's a tragedy, but it's real. Call this the depressing scenario.

So, back to the G20.

As it happens, South Africa, which is too small and too far away from the centres of action to really be a threat to anyone, could actually play a bridging role here. One of the reasons for regional insecurity is the lack of predictability and certainty in international relations. Mearsheimer dismisses liberal theories of international cooperation, arguing that they are secondary to raw power dynamics.

But surely it ought to be possible to minimise the extent of the conflicts? It's easy to get caught up in the current (depressing) moment, as it was to get caught up in the previous (hopeful) moment when Fukuyama thought history had ended.

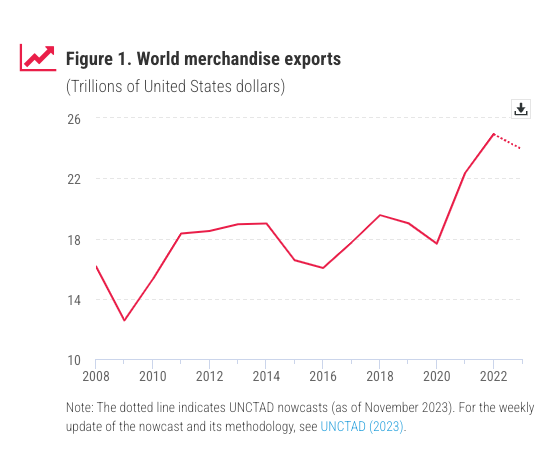

It's worth noting that over this period of supposed democratic decline, world merchandise trade volumes have increased by over 35% from 2014 to 2024. And they have increased everywhere. Services trade, much harder to measure, has exploded over the same period and is up, we think, around 50% over the same period, presumably courtesy of something called the networked computer. Trade remains above 50% of global GDP, which means that countries can seek regional hegemony if they want (they do) … but if they take it to extremes, they are gonna be only half as wealthy.

Anyway, get to it, South African diplomats. Now is the moment to demonstrate that you are the Springboks of diplomacy and dispel the reputation for being a chaotic, messy, lazy group of has-been political appointments with no interest and little organisational skill.

It's only 85% of the world you have in your hands.

From the department of difficult break-ups:

Google? Chrome? What happened dudes?

The US Department of Justice, along with a group of states, filed an initial proposal that would force Google to sell its Chrome web browser. It's not just Chrome; Google could be forced to sell the Android operating system. And make its services optional on Android Phones. And not be the default search engine on Apple.

So ... how bad is this for Google? Jury is out, literally, but Teiffyon Parry, chief strategy officer at adtech company Equativ, says "Chrome has served Google exceptionally well, but its loss would be a manageable inconvenience". Google stock has dropped, but not badly.

From the department of weird art involving bananas

Sold. One artwork of people going bananas

The infamous banana taped to a wall has been sold to crypto investor Justin Sun for $6.2-million. Sounds like a lot, but listen, he will get a free roll of duct tape, a certificate of authenticity, and - importantly - installation instructions. The actual banana is, as it happens, in fact, rotten. But he will eat a fresh banana, to illustrate the deeper meaning of the artwork.

The point was generally missed. The artist Cattelan himself described the work, called Comedian, as a commentary on society's relationship with value and art. He explained that the banana serves as a symbol, both humorous and thought-provoking, highlighting the absurdity of how art is priced. So its an ironic joke within a joke. It's so worth it!

From the department of really bad rebranding

Jaguar is now JaGUar

Jaguar, the car, has rebranded. But is it awful or brilliant, or brilliantly awful? Or maybe it doesn't matter. The point is that the actual image of the Jaguar is gone and in its place is a fancy new font with mixed lower- and upper-case letters.

As it happens, the problem is not the logo, its actually the car. First problem: the Jaguar logo is to designate the EV version of the car, but that's only coming in 2026.

Second problem: it's just not a very popular car anymore. Its technically designed to compete with BMW, but Jaguar sold 67 000 cars last year,and BMW sold 2.2 million. That is not totally fair - the Jaguar F-pace and the BMW 7 series are technically in the same category; both sell for about R2-million and neither are selling like hotcakes, as you would expect. But its possible to make great profits even selling small numbers of cars - just ask Ferrari.

Join the conversation