What if you don’t care what the “word of the year” is?

What is the world’s word of the year? What is South Africa’s word of the year? Why do we even care?

Toward the end of the year, i.e. now, an odd collection of interested parties coagulate to specify the “world of the year”. The idea is a favourite of dictionary sellers, particularly the online type, who are, for obvious reasons, pro words. It's a fun project and light enough to avoid direct mention of the problems of our day but relevant enough to imply them.

It's also a favourite of news outlets, either directly or as transmitters of the above. I suspect what they are trying to achieve is an insightful reflection of how this year will go down in history - the thing which will remind us of, say, 2024. So we are looking for the stand-out meme that was somehow the focus of attention and a summation of the main event of the year.

If that is the intention, the 2024 word of the year has been, IMHO, a blowout. Dictionary.com chose the word “demure” as its word of the year. What, I ask you with tears in my eyes, was “demure” about 2024? Certainly not the wars or the decline in global cooperation. Certainly not politics: incumbent parties all over the globe got absolutely hammered. From Japan to Bangladesh, to Sri Lanka, to Botswana, to the US, the political changes were so pivotal they were close to being historic or were actually historic. You name a place which had an election in 2024; the swings were just wild.

Dictionary.com chose “demure, " it said after its lexicographers analysed a large amount of data, including newsworthy headlines, trends on social media, search engine results, and more, to identify words that made an impact on our conversations, online and in the real world. They found a huge increase in searches for the word after a TikToker, Jools Lebron, uploaded a 17-second video titled "How to be Demure at Work", a chucklesome plea for dressing sensibly for work.

But by the standards of trending word searches, the 12 million searches for the word “demure” were impressive but not overwhelming. The word “YouTube” for example, was the most searched word in November this year on Google, with 1.2 billion searches. Although I have to say, Lebron’s TikTok is funny (love the “here’s your reality check diva, what’s the name you would like me to make it out to?” query.)

By the way, if the most Google-searched word is your standard, you are in for a disappointment. The top 100 terms on Google typically include only other sites, like YouTube above, and brand names. In November, for example, you have to go all the way down to no. 68 to find a non-brand name word, and that is “internet speed test”. For me, this would appear to make “frustration” as a summary for “I really, really want to throw my computer at the wall”, at least a contender.

The second dictionary announcing its word of the year was the Cambridge Dictionary, which chose the word “manifest”. It said “manifest” has shifted its meaning from revealing or demonstrating something clearly through signs or action into using visualisation or affirmation to help you imagine achieving something you want in the belief that doing so will help.

The word “manifest” was looked up almost 130 000 times on the Cambridge Dictionary website, making it one of the most viewed words of 2024. The word broke out during the 2024 Olympics in Paris, when a lot of medal winners cited the practice as a reason for their victory. That morphed into YouTube influencers using the word as a kind of “self-help” philosophy.

The reason I like it as a word of the year is a bit different. The gloomy side of me likes the ironic implication of self-deception and delusion that the word implies in its extended form. I mean, what is the difference between “manifesting” yourself as a billionaire and just indulging in a ridiculous, hopeful fantasy about becoming a billionaire? And although fooling ourselves is an ongoing human habit, it was a feature of this year in particular.

The old rival, the compilers of the Oxford Dictionary, have yet to make up their minds but have published a shortlist which does not include “manifest” but does include “demure”. It also does not include the word “brat”, which was one of the contenders of the Cambridge Dictionary's - among others' - lists. But as the Economist newspaper (as it likes to call itself) pointed out, if Kamala Harris had won the US election, it might well have been a hands-down winner. The “brat” is youth slang for “a little messy and likes to party”, and it was offered to Harris by Charli XCX, a British pop star. But “brat”, rather like its main beneficiary, has been a disappointment, and that probably helped sink the word.

The Oxford Dictionary has shortlisted “brain rot”, which I think is a fabulous word (or words) - see above, marking a year of delusion and misapprehension. The dictionary defines it as a “supposed deterioration of a person’s mental or intellectual states, especially as a result of overconsumption of trivial online content. Well, at the very least, that applies to me in spades.

Speaking of the Economist, it has chosen “Kakistocracy” mainly on the basis it seems of the appointments new US president Donald Trump has made to his cabinet. As South Africans, we know all about “kakistocracy”, which was an often-used term during the disastrous presidency of Jacob Zuma, symbolised somewhat by his seeming inability to say large numbers. Amusingly, the Economist says, “Kakistocracy has the crisp, hard sounds of glass breaking”, which would be a “good or bad thing depending on whether you think the glass had it coming”. Great word but in my opinion too localised and speculative.

The word or phrase that seems to me most obviously missing from the lists is "artificial intelligence", given how much has been written about it throughout the year, not to mention its potential significance.

In SA, the word I would choose for 2024 is “gnu”, the short form of the Government of National Unity and also, of course, the alternative name for wildebeest. SA’s new form of coalition democratic government is such a novelty and so untried, untested, and unknown that it's irresistible. I also love the fact that the gnu itself is such an ungainly, odd-looking beast, it reflects ironically on the government structure itself.

I also love the fact that gnu, despite being seemingly ungainly, is one of the most specialized and successful African herbivores. Could it be that this is a manifestation of our political future that will change our Kakistocracy and solve our brain rot? Ok, ok, calm down. Be real.

It's worth noting about these words of the year that they are massively hit-and-miss. For the Cambridge Dictionary one year, “nomophobia” made it in 2018 via a poll of readers, which notionally refers to the fear of not having your mobile phone. The word never caught on, although the feeling remains with us. Oxford Dictionaries chose “toxic” in 2018, which was a good choice but has since been incorporated into the language. Oxford chose "rizz" in 2023 which was kinda nuts, and Merriam-Webster selected "authentic" which was not.

The Economist suggested in 2018 that there is a tendency for words that seem new and interesting to disappear as they become generic and accepted. A lot of words of that period were depressing: “fake news”, “deplorables”, “snowflakes”, “remoaners”. The newspaper offered the advice that “if you are depressed by the vituperations of 2018, be consoled. Most will seem old in 2019, and be history by 2020”. The words may be depressing, but they won’t last, it said.

Like a lot of the Economist’s bold predictions, I think this one was wrong. Many of the words of the year have not only become incorporated into our lexicon, and in that sense have "disappeared" but they remain relevant if not outstanding. Others are definitively important and remain so, none more so than Dictionary.com's word of the year in 2018: “misinformation”.

That, my friends, has not gone away.

From the department of scary logistics

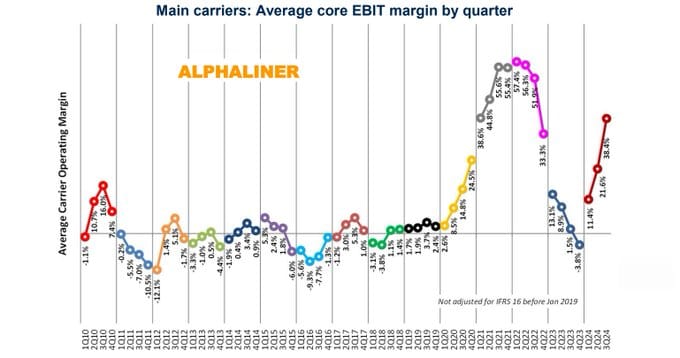

Carrier third-quarter margins reach 2021 levels!

According to logistics advisory firm Alphaliner, average operating margins for the leading container carriers (the nine largest companies reporting Earnings before Interest and Tax or EBIT) reached 38.4% in the latest quarter, equivalent to levels last seen in early 2021.

The leap in margins was of course a factor in the inflation outbreak of 2020 and 2021.

From the department of low energy

Celsius less than hot

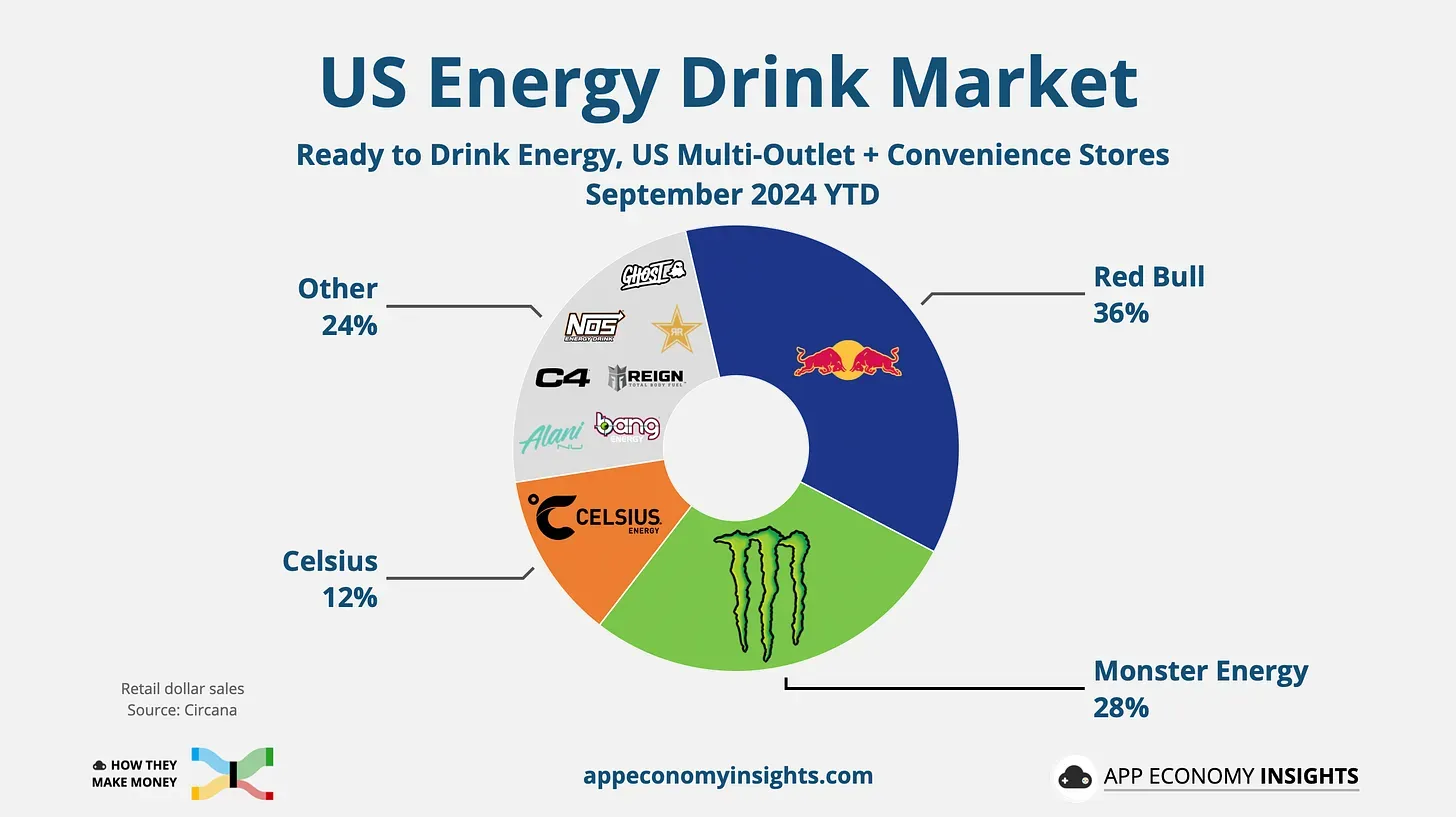

It's not all sunshine on the markets: the energy drinks company Celsius is now trading 70% below its May 2024 peak. Investors were betting that Celsius could challenge the legendary success of Monster Beverage - one of the best-performing stocks of the past 30 years. For many, it felt like a second chance to capture the exponential returns Monster delivered years ago, but with Red Bull and Monster dominating the market, Celsius is struggling to make headway.

From the department of AI being a thing

93% of 20-somethings say they use two AI tools a week

Google has surveyed 1 005 full-time knowledge workers, aged 22-39, who are either in leadership roles or aspire to one. It found that 93% of Gen Z respondents, aged 22 - 27, were using two or more AI tools a week — such as ChatGPT, DALL-E, Otter.ai, and other generative AI products.

Join the conversation