There is a widespread but terrible journalistic habit of ending analyses with “Only time will tell”. It's the ultimate cop-out; if something is too hard to decide, just say it's too soon to do so. There is actually a satirical compounded version which goes, “… that remains to be seen. And whether or not it will be seen, only time will tell”.

Often, however, time doesn’t tell, because by the time time does tell, nobody is interested any more. As I recall, five years ago, any analysis of Brexit that wasn’t passionately pro- or anti- (which was almost all of them) inevitably ended with the words, only time will tell.

But now that we are five years on from the formal start of Brexit in January 2020, it's amazing how few articles there are in the British press this week about this five-year mark because surely by now, time has told.

At a public level, proponents and antagonists of Brexit haven’t changed their positions, but there is a palpable sense of fatigue about the issue. When the issue came up in a BBC debate this week, Nigel Farage, head of the now rampant Reform party, described broadcaster and ‘remain’ advocate Alastair Campbell as “ the worst loser in history”. “You lost, it's over, move on,” Farage said, amid a frustrated discharge of sighing and eye-rolling.

Campbell, never one to lose an opportunity to mouth off, described Farage as “the worst winner” in the world. Farage didn’t want to discuss his most important legacy because even he knew Brexit had “made us poorer, it made us weaker, and it damaged our standing in the world,” Campbell said.

But is that right? It's been five years, FFS. Let’s look at whether time has told us something. Brits might be bored of the issue, but I think now is where it gets interesting - not only from the point of view of current British politics but from the point of view of economic theory.

When Brexit happened, I was convinced that it a) wasn’t going to be the apocalyptic disaster the anti-camp was arguing and b) it wouldn’t be the huge boost that pro-camp claimed either. Norway and Switzerland manage just fine, thank you very much, as European countries outside the union, so the calamitous disaster talk was overwrought.

There is arguably something about trade blocs that do benefit all their members - or at least that’s the economic theory. As far back as David Ricardo in the 18th century and even Adam Smith before him, economists have trumpeted the benefits of trade liberalisation, specialisation, market efficiency, resource allocation, and so on. So by withdrawing, the UK was surely going to suffer somewhat economically. Surely?

It turns out, I was wrong. At the broadest level, the real GDP growth of the UK was only a tiny bit lower than the Euro area, although it was noticeably lower than the faster growth of the EU as a whole. The cumulative difference with the UK’s European contemporaries was 0.1% and it's noteworthy that growth declined, really dramatically, in both the UK and the Euro area. Of course, the numbers are affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, but not significantly because although the UK declined more than Europe in 2020, it also recovered more than Europe. It was an international crisis after all. The numbers below, from the IMF, now include a five-year forward projection (good luck with that BTW) but even then the difference is trivial.

The point is, there remains a quandary. From the perspective of the pro-Brexit group, why have no benefits of the much-trumpeted sovereignty demonstrated themselves? And from the anti-Brexit point of view, why has the economy not suffered more?

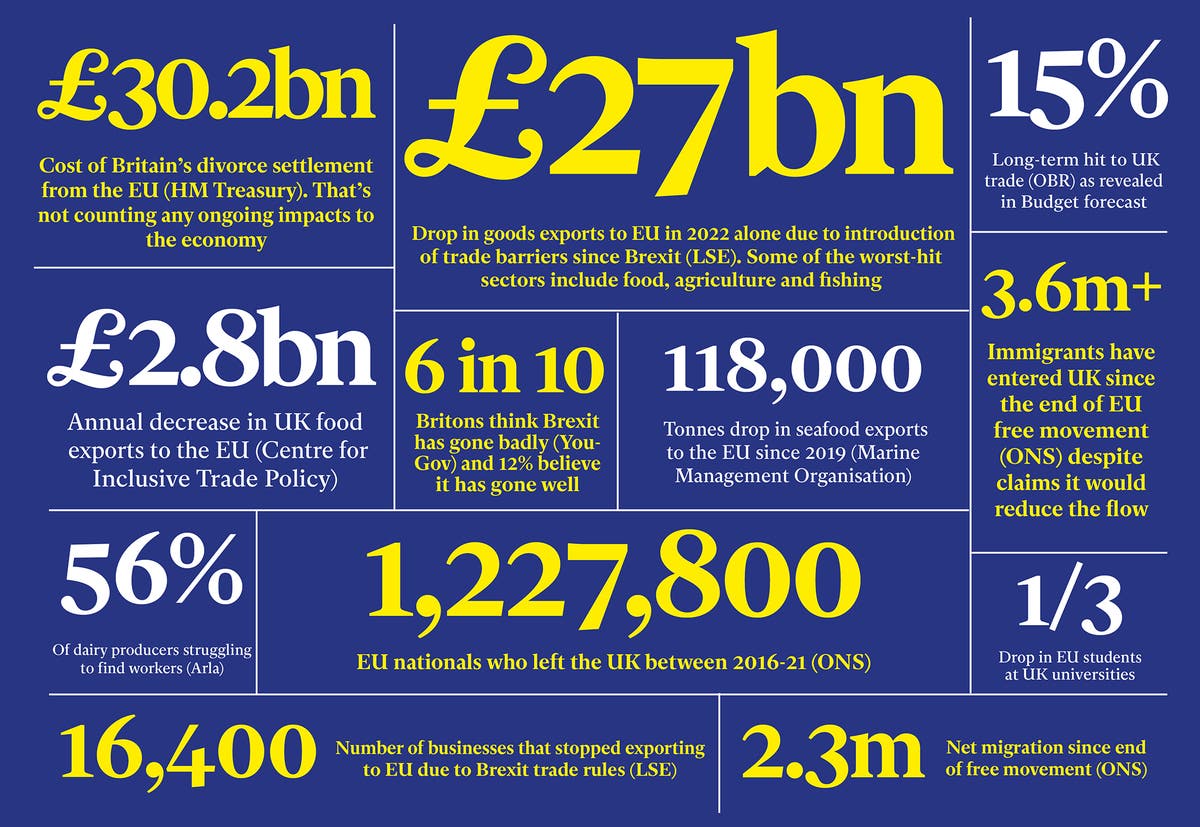

There are a couple of possibilities here, obvs. Perhaps the negative effects have still not filtered through (notwithstanding the IMF’s forward estimates)? In March 2023, the UK Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimated that Brexit could reduce the UK's GDP by about 4% in the long term compared to the result had it stayed in the EU. It presented a host of other potentially negative numbers too on investment levels and trade.

There are aspects of this analysis that point to future problems, but the truth is that this deeply pessimistic view is not justifying itself. Could it be that the problem is elsewhere?

And that proposition takes you down several different paths.

What if the benefits of being part of the EU from a trade point of view exist but are just not that great, especially since it's not as though trade between the EU and the UK stopped completely; it just got a bit grittier? Is it possible that there were potential gains to be made from being free of the excessive rule-based dictums of the EU, but the Tory government of the post-Brexit era just fluffed them? What if the problems are elsewhere? And what if - and it pains me to say this - it's just too soon to tell, either positively or negatively?

The truth is that there may be a bit of sense in all of these arguments. The most convincing is that the post-Brexit government tripped up. Start with four prime ministers in five years. And just to take one of them, knowing what we know now about Boris Johnson, how surprised are we that arguably the UK’s most deceitful prime minister in history dropped the ball?

You can see this too in the economic numbers. Gross debt as a percentage of GDP is up 18 percentage points since Brexit, compared to four in the Euro area. Wowzer! Under a Tory government! It is now sitting at just over 100% of GDP compared to the Euro area’s 88%. The UK is running huge deficits, even larger than the Euro area, which is saying something. On average, the UK's deficits (the amount of money the UK government is spending compared to what it is bringing in) were 3% of GDP prior to Brexit and increased to 7% per year after. And the UK’s new prime minister Keir Starmer is going to take it up further. No wonder the bond market is going nuts.

What about the argument that actually, the advantages of being part of the EU were always a bit overstated, or at least, the advantages were balanced against the disadvantages? One of the things I predicted (wrongly) was that trade between the EU and the UK would suffer. It has, but honestly not by much. You can tell because one frantically anti-Brexit newspaper, the Independent, has done a five-year review of Brexit, and even it has been forced to acknowledge the trade decline has not been significant.

Here is their graph on UK/Europe trade and they point out correctly that the import-export gap with Europe has widened. What they don’t point out is that exports to the EU from the UK were at a record in both 2022 and 2023. Globally, the UK’s balance of trade is in deficit to the tune of $3-billion a month, which for an economy the size of the UK is trivial and is exactly the same as the pre-Brexit period. This is even before the UK has managed to win free trade deals with a host of countries out there, notably the US (more Tory post-Brexit-fluffing), which now is not going to happen any time soon. The big point is perhaps that the UK economy - and economies of the developed world in general - are essentially now rooted in service businesses: banking, advisory, auditing, retail, property etc. And unlike manufacturing economies, trade deals just don’t help in the same way … and don’t hurt as much when they are lost.

This brings us to the possibility that the big problems have yet to exhibit themselves. Here the Independent review does throw up some interesting numbers - and are such a big irony. Between the Brexit referendum in 2016 and the end of free movement in 2021, approximately 1,227,800 EU nationals emigrated from the UK. This was to be expected; the end of the free movement of EU nationals, who brought so much European culture to the UK, was always going to result in their departure. But what has been a surprise is that their exodus has been massively countered by immigration from India, Nigeria, Pakistan, China and Zimbabwe. Net migration is up 40% since Brexit. The UK has substituted its European identity for an essentially Asian/African orientation; that’s no terrible thing - but the quantum of the increase is a surprise since Brexit was essentially won on the notion of Britain for the Britons.

And that leaves one thing: maybe the problems of the UK have nothing to do with Brexit; they lie elsewhere. Campbell said Brexit “damaged our standing in the world”. The Independent quotes former deputy prime minister Lord Heseltine saying that nearly five years on “it has destroyed Britain’s leadership in Europe just at a time when there was a critical need (for it), it has closed off opportunities for the younger generation to share in the benefits of Europe and it has denied Britain’s industrial base access to the research and policies of Europe”.

This is a hard point to argue because it's so impressionistic. My sense, coming from a distance, is that there is some truth to this. But I suspect there is still a lot of support for Farage's perspective in the BBC debate above, that “We are free and not part of that Eurozone which is collapsing around its ears. Rejoice”. I suspect it makes a difference to Brits that the Eurozone is about to elect serious rightwingers to its parliament. Brits fear the old German predicament of being allied with the Austrian empire, which statesman Otto von Bismarck described as "being shackled to a corpse".

But there is also a touch of residual British snobbery that underlines the notion of “our place in the world”. For toffs like Lord Heseltine, you get the feeling that essentially he believes, in the best of all possible worlds, Britain really should be running Europe.

But if that’s the case, it could start by running Britain better. US growth has outpaced both the UK and Europe post-Brexit; check the graph above, the US is now growing twice as fast. Brexiteers look over the Atlantic and feel the UK should and could be getting some of that juice because Europe never will. But, for some reason, five years on, the UK seems no closer to discovering the intrinsic economic prowess of the US than before.

I know, I know; I’m from South Africa; we are not ones to talk. But you know, just saying. 💥

From the department of things that really don't add up

From the department of things you don't want your dog to eat

Chocolate-coated vet's bills

A fun story from newsletter Morning Brew about how vet bills in the US are rising twice as fast as inflation - and all the fingers point to Mars (the makers of M&Ms), which is now a major owner of vet clinics. Without the revenue from the said clinics, Mars would be ready for … um … euthanasia.

From the department of inevitable decline

Deaths in the US expected to exceed births 10 years earlier

If there is one topic that has really become a major trend of the 2020s, it is demographics. Countries that have for years assumed population growth will increase for decades are suddenly realising that it's not working out that way. Hello, China. But now we can add the US to that list.

Thanks for reading this post - please to send it to anyone who might be interested. It's free, as you probably know, for the time being. Just ask your contacts to put their name in the sign-up above - or subscribe. By all means, comment on the post below. Catch you next time.

Join the conversation