Some time ago, I was granted a one-on-one interview with Bill Gates, the renowned entrepreneur, healthcare buff, and global philanthropist, as everybody knows. To say this was a rare honour would be a massive understatement - Gates does sit down with journalists now and then but not often.

In all honesty, I think I fluffed the interview. I didn’t manage to elicit any really fresh information and although the subsequent piece in Business Day was informative and interesting, there was nothing in it really to write home about other than making my colleagues jealous!

The problem was that the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation had just started to increase its focus on malaria since the Foundation had made some quite amazing strides, and I suspect Gates wanted to encourage African governments, including South Africa's, to put their shoulders to the scrum and push. Malaria is a complicated disease and the Foundation must have been worried that I would ask stupid questions so they insisted on a series of pre-interview briefings.

The consequence was that by the time I finally sat down with Gates, there was almost no question I wanted answered that hadn’t been addressed. But still, it was a blast to speak to someone as eminent as Gates just for a moment. There was a topic we touched on but didn’t get back to that I dearly wish we had discussed more, which was whether improved health care is a necessary precondition for development (Gate’s view) or whether it's a consequence of economic development (my view).

But I felt constrained to focus on malaria because this was the reason I was through the door and, after all, the topic is genuinely interesting. Just to divert quickly, malaria is now basically an African disease, and a particularly cruel one since the principal victims are children. If you survive into adulthood, you probably develop sufficient immunity to continue surviving, although it's never beaten as measles has been (or was). Most Africans in high-prevalence areas get malaria hundreds of times in their lives (one of the many facts I didn’t know before the interview).

But things are getting better. Between 2001 and 2019, malaria deaths declined by almost half, sparing around half a million people. And better yet, while global malaria deaths have dropped by around 47%, the deaths of children under five have declined by 60%. How did they do that? Partly through distributing insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs), artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs), rapid diagnostic testing, and improved case management.

How much of this is attributable to the Gates Foundation? Well, it's more than a coincidence that the Foundation started its efforts in 2000 and that it spends roughly the same amount on anti-malaria programmes as it does on all other expenditures. It's astounding that Gates and/or the Foundation haven’t been given a Nobel prize for this effort - just one of its many efforts - but I know exactly why not. It's because Gates is considered a philanthrocapitalist, and his solutions tend to be technocratic. Or to put it another way, they work, which tends to embarrass all the hundreds of highly paid government and NGO people whose solutions tend to be bureaucratic. That’s just my prejudice, but I bet it's true.

Anyway, for someone who tends to be looked at slightly side-eyed by the NGO community, it was interesting that Gate’s position on the sequence of development was more in line with the NGO community than I would have guessed.

As I said, we didn’t go into it in depth, but I can more or less surmise what his argument might have been, going something like this: Healthier populations are more productive. Since that is true, it makes sense that healthy populations are a precondition to economic development. You might also say this is demonstrable from a historical point of view because as malaria has declined, African GDPs have exploded.

But there is even more to it than that: lower health risks tend to reduce economic uncertainty, improve the quality of education and decrease spending on health care. Moreover, they reduce child mortality which improves demographic transitions through lower fertility rates.

The counterargument is that improving healthcare is expensive so without economic development, it's impossible to make serious inroads into improving health. Research, such as it is, tends to support this argument. Celebrated academics Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson looked at the effect of life expectancy on economic growth around the world in the 1940s and found no evidence that the large increase in life expectancy raised income per capita. As Acemoglu has argued throughout his career, institutions, governance, and complementary investments (like education and capital development) matter greatly.

Logically, you can see how improved healthcare can work against development since larger populations following healthcare improvements increase demands on the healthcare systems in the short term.

But isn’t this all just splitting hairs? The issue is integrated and iterative: development causes better healthcare causes better development (one hopes) and so on. Effective health care is not always the first step, but without it, sustained, equitable development tends to stall. It’s less about the 'chicken vs the egg' and more about 'the engine vs the fuel', ChatGPT tells me. You can start the engine without great healthcare, but it'll sputter out pretty fast.

Whatever the case, it's obviously working.

This graph shows GDP growth of the major African countries, all roughly equatorial, as you might expect, hit by malaria before the battle to address it and in the two decades afterwards. The change is just phenomenal. GDP growth in malaria-hit countries, chosen more or less randomly, was 1.6% in real terms per year. That exploded to an average of 5.2% in the following decade, which is more or less the same as the global emerging market average. In the subsequent 14 years, the countries grew by an average of 3.7%, a little slower than global EMs but a bit faster than the continent as a whole.

There could be lots of reasons for that of course. But I’m writing this not because of Bill Gates but in response to Gate’s fellow tech bro Elon Musk because I’m astounded and heartbroken and outraged that the US has now summarily smashed George W. Bush’s fabulous contribution to humanity: Pepfar, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief.

The other biggest contributor to the fight against malaria was the US government, which matched the Gates Foundation’s contribution over the years, not only to malaria but also to AIDS and TB, and strengthening health systems in general. Pepfar was launched a few years after the Gates Foundation began its fight against malaria, contributing to the battle against malaria, a door which Gates opened. Much of the focus is on AIDS, of course, because it is brutal and because it is now essentially a manageable chronic condition. But global deaths from AIDS are 1.5 per 100,000. Malaria is still clocking in at 14 per 100,000.

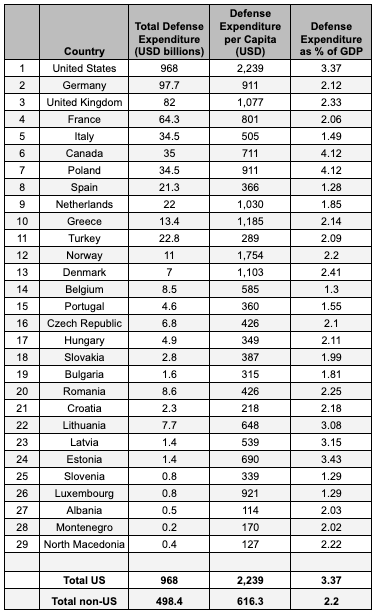

US President Donald Trump is constantly whining about how much more the US contributes to national defence compared to its NATO counterparts, previously referred to as “allies”. As far as it goes, this is more or less true. The US defence budget is 50% higher than most Nato nations.

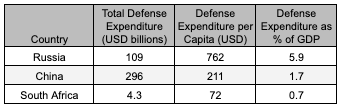

But on the flip side of that coin, the US contributes only a tiny amount to development aid as a proportion of its GDP compared to other Nato members - and this was before Musk took his chainsaw to USAID. The US does contribute the most in absolute terms, but actually not that much more than Germany, a country a third of its economic size. As a proportion of its GDP, US expenditure on development aid squeaks into the top 20. And just by the way, look at the ridiculous comparison above between aid budgets and defence budgets.

What was particularly galling was the joy with which Musk did it, saying his Doge unit had “fed USAID into the wood chipper.” The decision was based on the notion du jour that there was horrible overspending and waste, which of course is partly true. No good deed goes unpunished, as they say, and lots of vultures flock around easy money. Obvs. But equally obvious is that something - a lot - was working.

Since the destruction of USAID, Musk's car company Tesla has been in freefall on the stock market and there has been considerable vandalism of these vehicles around the world. This is horrible, but here is the weird thing: Musk had the gall in his recent interview with Fox News' Sean Hannity to claim, "I've never done anything harmful."

Well, I’m afraid if you suddenly and summarily destroy the tiny, pitiful access that dirt-poor people in Africa have to life-saving drugs; if you harm health programmes that are transparently working; if you callously destroy the income of people who have devoted their lives to trying to do a little bit of good, then I’m afraid you have done something harmful.

And harmful not only to them but to the US and its interests and its reputation. For a generation of people around the world, myself included, the US was the mansion on the hill and generally speaking, with notable exceptions, a great force for good. In the space of a few months, that has been destroyed.

Congrats.

From the department of deep concern about the unflushability of cell phones ..

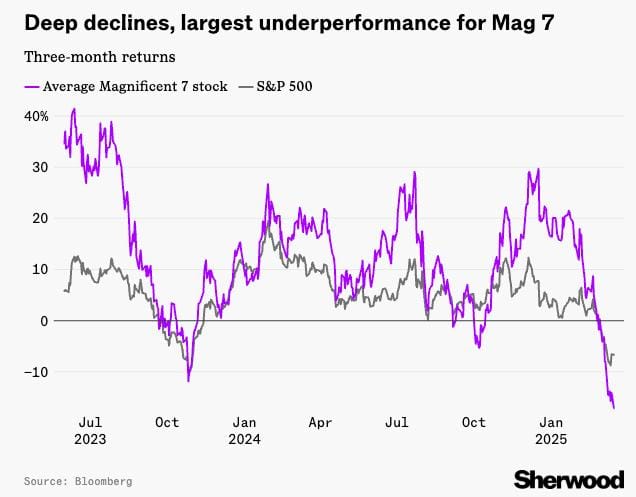

From the department of MAG Seven - or should that be MUG Seven?

From the department of you thought you were chasing Snorlax, but it was chasing you ...

From the department of dumb and dumber...

Thanks for reading this post - please do share if you have a friend (or enemy!) you think would value it, and ask them to add their email in the block above - its free for the time being. Also, please take my survey if you have a mo - it really only takes a minute. Till next time.

A reader asked me to post a more complete breakdown of Nato defence spend - here it is, as at 2024. Interesting that Canada and Poland outspend the US on a % of GDP basis - and that countries that could easily do more, Spain, the Netherlands, and France, pull down the average badly.

T.

And just to increase the frame a bit ...

Join the conversation