You have to feel a bit sorry for Schrödinger's cat. From Schrödinger's perspective, the situation is uncertain. But from the perspective of the cat, while things are also uncertain, the consequences of said uncertainty could be horrible.

And isn’t that the thing about uncertainty? It's not the fact of uncertainty that is worrying; we all know things are uncertain. But what concerns us, or should, is just how bad things could get if they head in that unfortunate direction.

An old Schrödinger’s cat joke goes that eventually Schrödinger couldn’t stand the suspense any more, so he decided to open the damn box. Turns out, curiosity did, in fact, kill the cat.

The world enters 2025 in a state of high uncertainty. We know this because there is a huge industry out there trying very hard to make intrinsically uncertain things more certain. First they measure the current level of uncertainty.

It will surprise exactly no one that the current levels of uncertainty are extremely high. One rather clever index sifts through the Economist Intelligence Unit’s country reports and counts the times the word 'uncertain' is mentioned. The country reports are consistent, annual reports on most of the largest countries around the world, sold separately from the magazine itself.

This is the result:

Unsurprisingly, the level of uncertainty shot up during Covid-19. But even discounting that period, the level of international uncertainty is on a very steep upward trajectory despite the return to what might be described as normal levels of uncertainty following Covid.

Does this measure tell us anything? Maybe the writers of the Economist Intelligence Unit's reports have become less confident about their predictions so they are hedging their bets by describing more of what they write about as 'uncertain'.

However, this report does mirror others out there. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) produces something called the Global Economic Uncertainty Index, which feeds into its World Economic Outlook. In keeping with our theme, the latest World Economic Outlook is entitled: "Brace for uncertain times".

This is the map of the Global Economic Uncertainty Index:

On the face of it, there is a rather astonishing match between this index and the 'uncertainty' word count in the EIU reports.

From a macro point of view, there is another way of looking at uncertainty, which is to compare economists’ predictions on key metrics and then check at the end of the year how accurate they were. The St. Louis Federal Reserve has crunched the numbers on 21 years worth of economists' forecasts collected by the Blue Chip Survey of Professional Forecasters (I am not making this up. Such a thing exists). This tracked the widely-followed survey of firms, which includes all the big names, including Bank of America and Goldman Sachs, as well as top manufacturers and insurers, from 1993 to 2024.

The results are so bad, they are funny. Market Watch writer Steve Goldstein did a simple calculation of the percentage of years over the past two decades that the average expectation matched the actual outcome. He looks at each of the key economic indicators and determined that the Professional Forecasters would have been more accurate just flipping a coin.

But even by this terrible standard, 2023 was a horror show for US forecasters and 2024 wasn’t much better. In early 2023, the National Association for Business Economics (NABE) revealed that 58% of economists anticipated a recession within the year. By July, the US Federal Reserve announced they were no longer forecasting a recession in 2024. Good thing too because US GDP growth kept on surprising on the upside and seems likely to end the year at just below 3%. That’s not stellar but it's a long, long way off from a recession.

One way of reading this is that economists and their complicated models are totally missing the point and getting everything upside down and backwards. But another way to read it is that economic forecasting is just getting harder. Or, to put it another way, the quantum of uncertainty is increasing.

There are ways of measuring other aspects of risk, too. Oddly the one we don’t need is a geopolitical risk indicator because it's so just damn obvious. There is a measure called the Geopolitical Risk Index (GPR) which tallies the number of times newspaper articles discuss geopolitical tensions, risks and conflicts. And surprise! These are strongly up. Hello Sahel, Ukraine, Russia, China, Middle East, etc.

Nor do we need to know that the election of the US’s most unpredictable president, Donald Trump Esq adds to global uncertainty. Not only is it hard to imagine what he intends to do as president; it's hard to understand what he is saying. Just consider a press briefing in Rancho Palos Verdes, California, just before the election where he said the following: "You have millions of gallons of water pouring down from the north with the snow caps in Canada and all pouring down. And they have essentially a very large faucet. And you turn the faucet—and it takes one day to turn it: it's massive, it's as big as the wall of that building right there behind you. And you turn that and all of that water goes aimlessly into the Pacific. And if they turned it back all of that water would come right down here and right into Los Angeles. They wouldn't have to have people not use more than 30 gallons”.

Oh, crapstix. Just to be clear, the Canadians do not have a big tap, the size of a building, that could pour water into Los Angeles, almost two thousand kilometres away to relieve water rationing. Since his fanciful Canadian tap situation is unclear, how uncertain do we regard whether Trump will push ahead with his threat to lift tariffs by 10-20% on all imports, rising to 60% for Chinese goods? Were those threats just the opening gambit in a negotiation? If he goes ahead what sectors will bear the brunt? And who will retaliate? And by how much?

Politically, what is odd about 2025 is how few big elections there will be, particularly after the festival of elections in 2024. Germany, Canada, and Russia have scheduled elections, but almost everybody else is still reeling from the results of last year's polls and trying to make sense of what happened. Hello, France, South Africa, and a host of others.

Even though elections are considered high uncertainty moments, the very craziness of the results with incumbents being thumped almost everywhere, has probably meant that the level of uncertainty has not declined substantially.

So, what to do? Well, it is hard, but ChatGPT tells me that it helps to create a resilient mindset, embrace change, focus on what you can control, develop scenario planning, be iterative in decision-making, diversify, and gather information effectively. That all seems sensible, if slightly obvious.

It's like the joke about Schrödinger's cat. It's either funny or not funny. Until you tell it to someone. Then it's either a joke or not a joke.

This is the thing about uncertainty and Schrödinger's cat: you need to think outside the box.

From the department of slightly too much honesty ..

Boomers stay boomers

Great read about how boomers are drinking too much, taking too many drugs, having too much sex, and getting arrested in larger numbers than ever. You can take the boomers out of the youth bracket, but they still boom.

And as if to drive home the point. Consumption of red wine by 'less booming' generations in France has fallen about 90 per cent since the 1970s!

From the department of Siri, you have the con ..

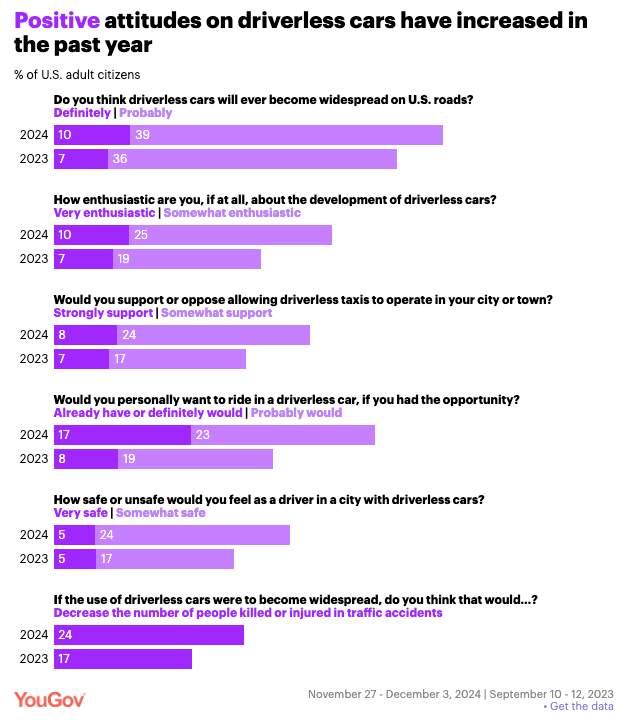

Attitudes toward driverless cars are improving fairly quickly now, but not quite there yet.

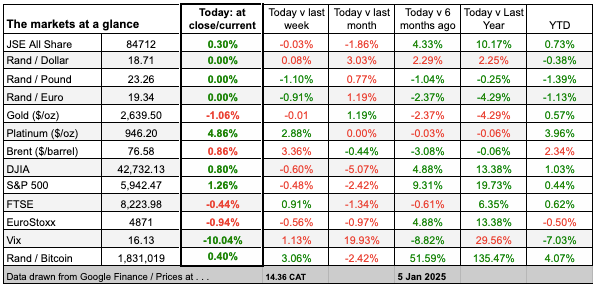

From the department of what globalisation crisis? ...

And what economic crisis in China?

Thanks for reading this post - please pass it on to anyone whom you think might enjoy it; they can just add their email address to the signup above; no pack-drill. 💥

Join the conversation